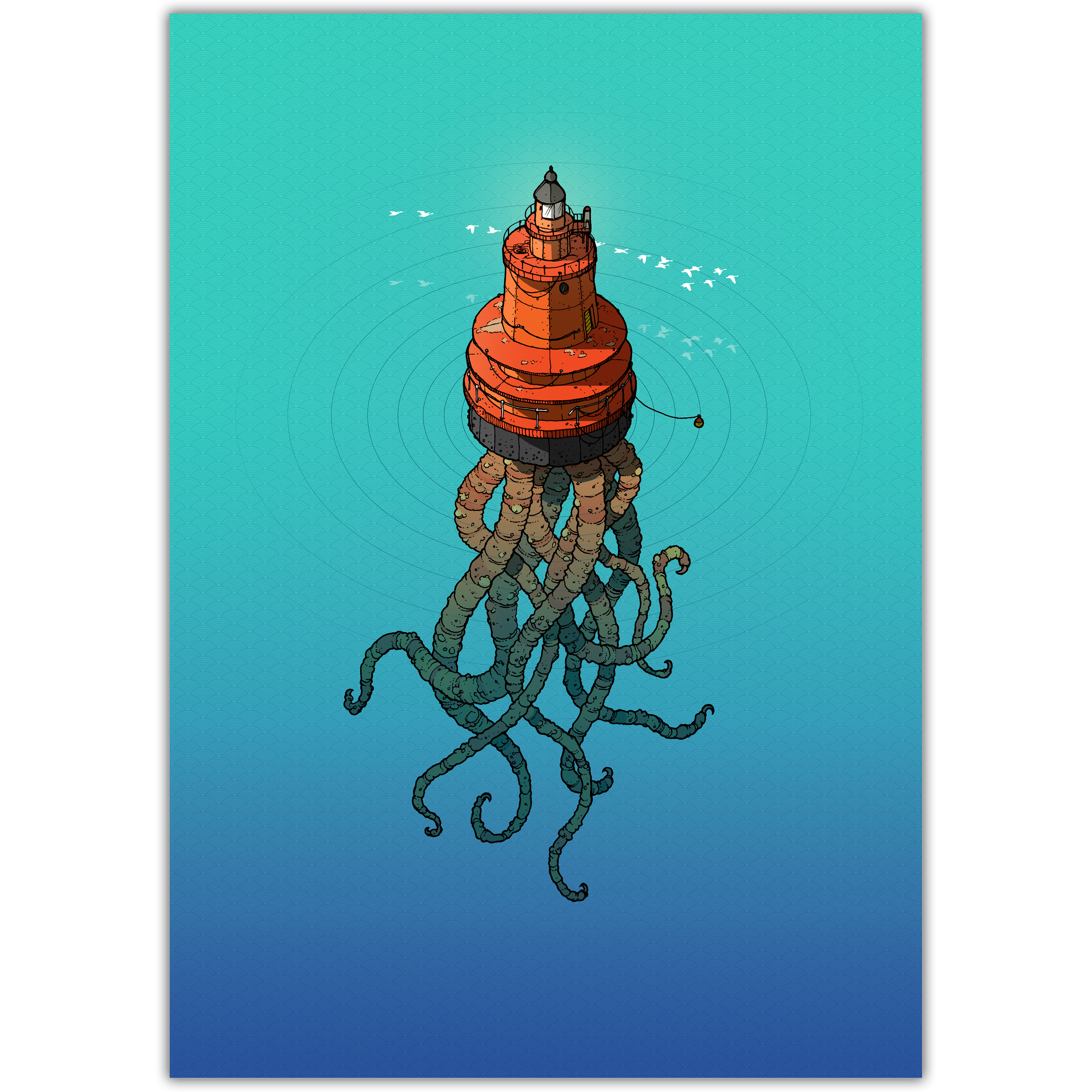

The Innsmouth Lights

Originally begun on social media, written post-by-post, 140 eldritch characters at a time, here is my Lovecraftian tale of the Massachusetts town of Innsmouth, its strange history and the recounting of the lives of its inhabitants.

Chapter One

The Innsmouth Lights, protecting the New England town of Innsmouth since 1642. Guaranteeing safe passage for vessels all year round, except on those peculiar days when the membrane between this world and others becomes thin and stretched.

Just seven nights remain until the Winter Solstice. Time for the people of Innsmouth to nominate their candidates for King and Queen of the Oceans.

Innsmouth Lightship No 01. Betty Tilley pilots the 01. Keeping the shoals safe for shipping at low tides. She painted the ship in dazzle camouflage last winter, helps avoid unwanted attentions from the depths. If you know what I mean.

The bell on the Black Reef rings loud tonight. The wind is up, and the heavens are hungry.

Dawn brings news of a wreck. Masts prick the shoals like needles in a cushion. Of the crew there is no sign.

The Bishop knocks on every door West of the Rock in Innsmouth tonight, tallying the nominations. East of the Rock, the Cleric does the same. They’ll meet at midnight to tally the numbers. Tomorrow the King and the Queen of the Ocean will be announced to the town.

The Bishop and the Cleric add up the votes. Tomorrow the two young townsfolk and their families will be notified.

West of the Rock live the fisherfolk. To the East, the whalers.

The Pelagic. Innsmouth’s only Tugboat. Piloted by Robert Coppin, whose mother was a fishwife and whose father was a whaler. He’s always felt like he was between people and places.

John Chapman, a whaler’s son, and Jennifer Cochrane, a scallop dredger’s daughter, will be this year’s King and Queen of the sea. Tonight the town, East and West, prepare a feast for their families. Halibut and octopus will be the heart of the festive meal.

Whale irons. Two flued. English. One flued. Toggle. Explosive. Lance. Spade.

It’s quiet across the town today. Last night’s feast and revelry has left people delicate and moody. On the Black Reef, Degorius Priest unloads timber from his clinker-built skiff. He’ll spend half a day there, between tides, building for the solstice ceremony.

Artefact: Granite cephalopod pendant. Probably 17th Century. Found in the footings of the wharf during rebuilding work in 1837.

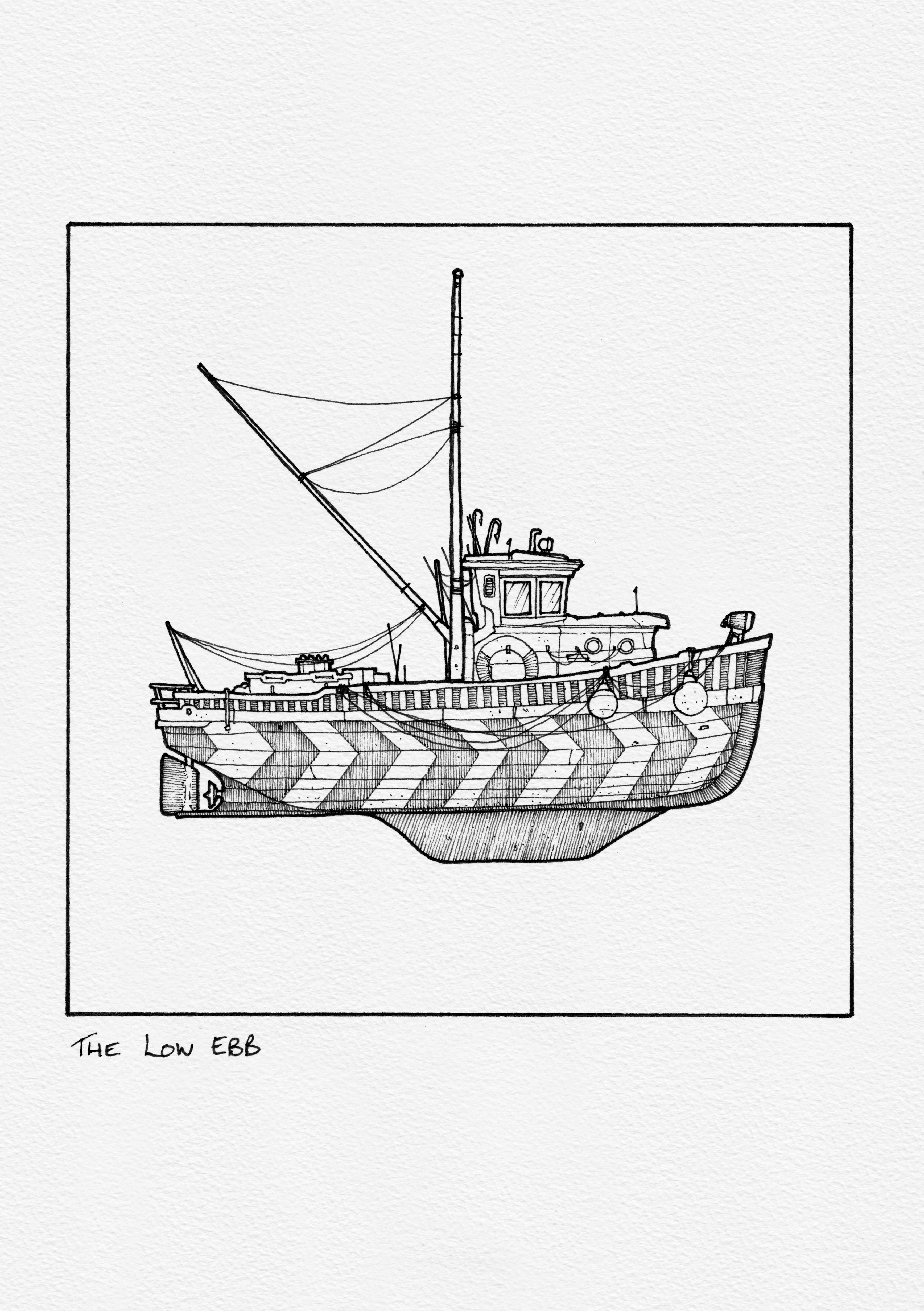

The Low Ebb.Moses Fletcher inherited the Low Ebb from his father twenty years ago. Since then he’s made a living (barely) fishing for cod, ling, and herring off the Far Banks.

The solstice sun creeps over the horizon, weakly illuminating the rooftops of Innsmouth, through a veil of fog.

As noon approaches, all the townsfolk make their way to the harbour wall. They are dressed in their Sunday best, the whalers all wearing their harpoon brooches, the fishers all wearing a pin of the sealamb. They stand in silence looking out toward the shoals.

The King and the Queen of the Ocean walk towards the dock, flanked by their parents. As they reach the harbour a piper plays a mournful tune.

The Queen is wearing a white knitted dress adorned with pearls. On her head sits a gilded shark’s jaw crown. The King wears an oiled leather tunic, inlaid with rings of iron. On his head, a nautilus shell trimmed with jet.

John and Jennifer kiss their parents goodbye. John’s mother sobs and cries out, her husband holds her tightly. The King and Queen descend the steps of the dock to the waiting rowing boat. The boat is decorated in white shells and pearls, and at the stern a gaff and a harpoon are crossed.

Degorius Priest pushes the boat away from the dock with an oar, and slowly begins to row. The crowds of townsfolk chant softly as the King and Queen make their way to the Black Reef.

Don’t you hear the old sea growlinDon’t you hear the wind a howlin

Don’t you hear the captain pawlinDon’t you hear the pilot bawlin

Only one more day hungryOnly one more day an empty net

The King and Queen we give to theeOur two souls a gift for the sea

Let’s not hear the old god callinLet’s not see the waves a thundrin

The King and Queen we give to thee

The boat reaches the reef as the chanting stops. Degorius helps the children on to the rocks and seats them in the stout wooden thrones he’d built two days earlier. John and Jennifer are quiet and calm. The air and sea as still as oil.

Degorius rows back to shore alone, reaching the harbour just as the town’s clock began to strike noon. He looked back out to the reef some three hundred yards away, the King and Queen little more than dots to his ageing eyes.

The townsfolk hold their breath as the bell chimes – ten, eleven, twelve. For a second it seems as if time stops, and then…

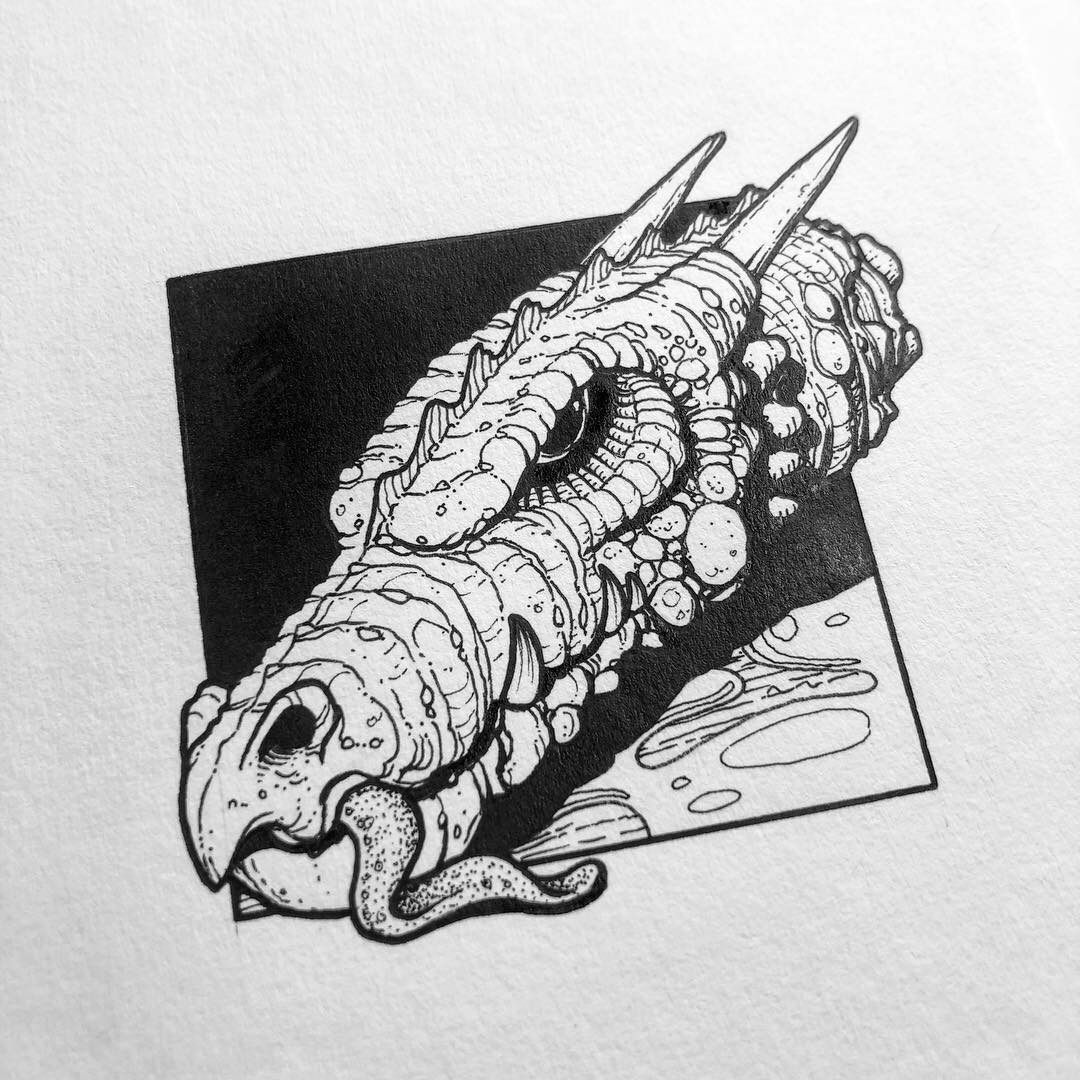

The sea behind the reef erupts. A great beast surfaces. It’s outline blurred by sea spray and a thrashing of tentacles. Eyes surround a gaping, many-toothed, jaw. Membranous wings shudder and snap. There’s no distinction between head and body, just a leathery mass.

The creature searches the reef, its eyes swelling and twisting, never blinking. The King and Queen, paralysed with fear, soaked by the sea, have its attention now. It leans, or possibly the world tilts, until its shadow falls across them.

The townsfolk know what comes next, and almost all of them avert their eyes, wanting to shut out the horror for another half-year. There’s a wrenching sound that echoes in rock and bone alike, the creature pauses, its mouth becomes a maw – endless and black.

And then, another noise, a man-made sound. A harpoon launches from the end of the whalers quay. Huge, much larger than those that take down the sperm and fin whales, it arcs across the sky. The creature is oblivious, giving no thought to a threat from mere mammals.

The iron spear, its tip multi-barbed and laden with explosives, strikes the creature in the centre of its middlemost eye. A shriek shreds the air as the creature hurls itself backwards – just as the harpoon detonates. The blast rends the beast in to pieces.

Gelatinous flesh, brittle bone, and fragmented teeth erupt in to the air. Silence falls across Innsmouth, before a deep, pulsating, thrum drowns out the sound of the creature falling back beneath the waves. The sound builds. Louder than the most terrifying thunder.

Cracks appear in the fabric of the town. Tiles fall from roofs, the spire on the church cracks and falls to the ground. The whalers’ wharf falls gracelessly in to the sea. As the people of Innsmouth prepare to take cover, another sound gains their attention.

A keening, high pitched whine. It emanates from the Black Reef. Where the creature was, now there was an absence, not simply of the beast, but of anything. And the absence grew larger. An impossible, expanding, sphere of nothingness. People fainted at its wrongness.

Still it grew. Those still standing ran for their lives. A primal need in their very flesh to be wherever the absence wasn’t. And still it grew. The sphere expanded quicker now, reaching the town and its people. It swept over the harbour and enveloped the seafront.

The church, the Chapel, the pubs, the boat makers were all subsumed. The membrane of the aberration sped across Innsmouth, accelerating out from where the creature died. Now a sphere over a thousand yards across. All of Innsmouth was consumed.

Still it grew. The wrongness expanded out, miles to sea, embracing the four lighthouses that spread in an arc from the harbour. The village of Bedfordthorpe, Threkeld Farm, and the dairy at the Needles were all vanished in to nothing.

Then, miles in diameter, the sphere paused. It shimmered in the grey light of the solstice sun, its surface slipping from a petrol dappled rainbow, to a nacreous white.

Everything stopped.

The very air paused. Birds stopped still in the air. Waves paused as if made of glass. A fish, caught mid-leap, hung above the sea. Time did not pass.

An eternity could have elapsed, or less than a heartbeat. The sphere vanished, simply ceasing to be. The only evidence of its disappearing the howling of the wind as air rushed in to fill the space it occupied.

Of Innsmouth, no sign remained. A perfect arc of Massachusetts coastline had been eaten by the event, and the sea crashed in to replace the land. Waves heaved back and forth against the virgin shore before settling in to a new arrangement for map-makers to ponder.

The sea forgets quickly and showed no sign of the phenomenon that had robbed New England of a part of it. The air calmed. Birds flew. Fish swam. Waves lapped gently.

Innsmouth was gone.

…

…

…

Time did, or did not pass. The sun and moon raced across the sky, or hung motionless against an unmoving gale.

…

…

…

Eventually, Innsmouth awoke, an island, in a strange and unfamiliar sea.

•

So ends Chapter One of the telling of Innsmouth. A town once of Massachusetts, now an island in an unfamiliar ocean. A town cleft in two by The Rock. A town of fishers and of whalers. A town beholden to a beast.

•

Chapter Two.

The immediate aftermath of the event was one of joy – finally, after generations of being in thrall to the creature, it was dead. When the children – the King and Queen of the Ocean were found alive, the town felt doubly blessed.

It took little over an hour for the townsfolk of Innsmouth to discover they were cut adrift, now an island. Word came from the dairy farm over the hill. Half its cows and a third of its pasture gone.

People looked at each other in disbelief and shock. William White, Shoalkeeper and head of the fish folk, instructed The Leviathan and The Low Ebb to set out immediately and survey the coast.

Bartholemew Gosnold, head of the Union of Whalers, asked the same of The Tidal Pull and The Maelstrom. The fishers set out clockwise, the whalers – widdershins.

In the town, by the rock, recriminations began.

William White berates Bartholemew Gosnold. Shaking with rage and contempt. Gosnold reacts not. Impassive, like the granite quay they stand on. White leans in, spittle flecking his chin.

“How could you be so arrogant? How could you be so foolish? Look at what you’ve done!”William White seemed to vibrate with barely contained fury.

“And would you have us just continue? Year on year, generation by generation. Giving up our young to that beast? Sacrificing the best of us. Our children, William‽” Gosnold spoke quietly, but coldly, anyone but the Shoalkeeper would wither at his words.

White sneered. “And now what Whaler? What of our children now? What of us? Adrift! Lost! Castaway Lamb-knows where. How has this improved our lot?”

“You know nothing William. We know nothing. Hold your tongue and your spleen until we do. This talk helps nobody.” Gosnold turned and walked away, leaving William White alone at the quayside. His milk-pale face covered in a sheen of anger.

At Midwinter’s observatory, Kellam was making a discovery.

Kellam Midwinter checked his calculations, again. He leant on his knuckles on a table littered with maritime maps, star charts, and notebooks. The pencil Kellam was biting on finally snapped, breaking him out of his thoughts.

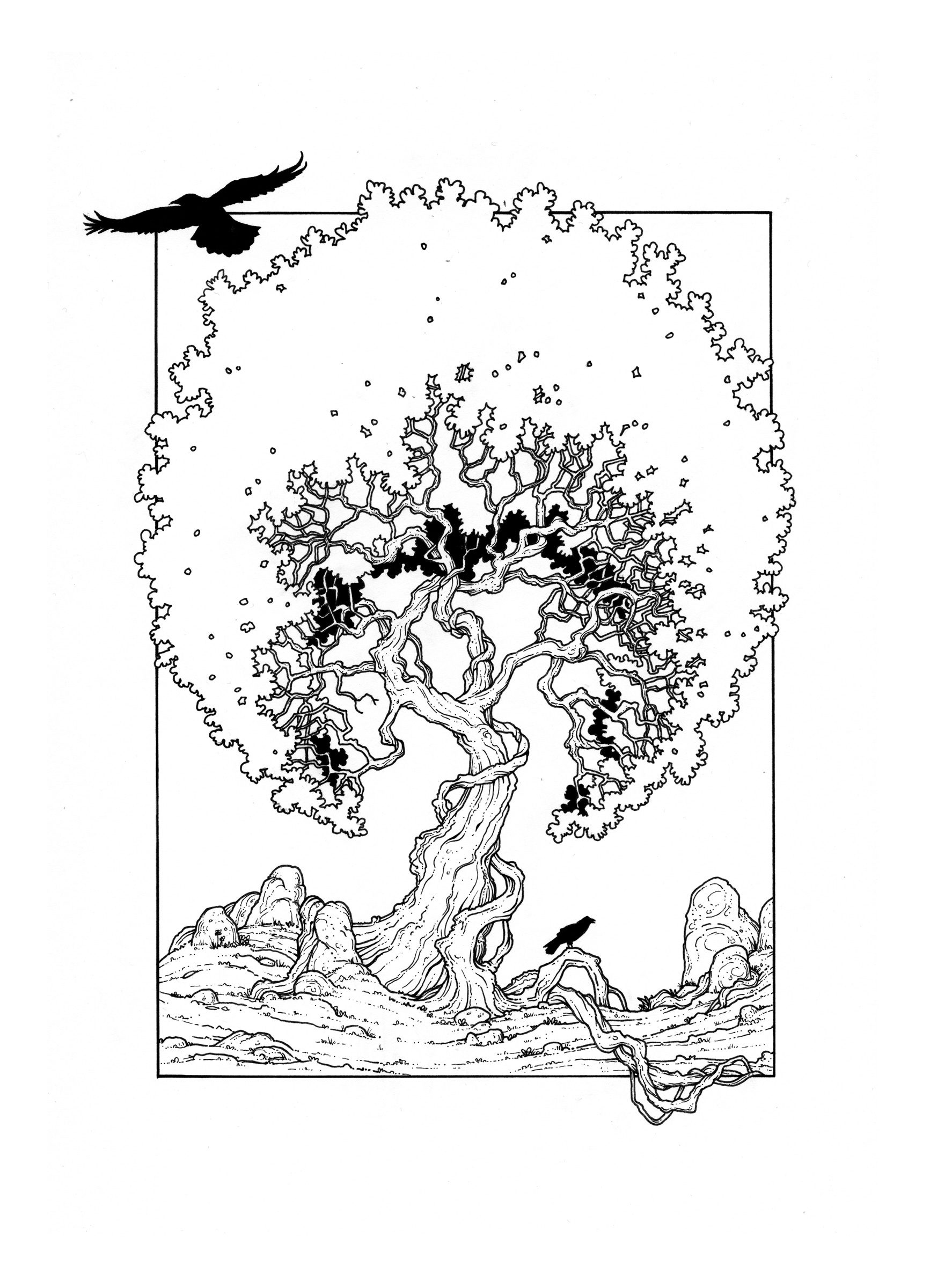

“Mrs Millward”, Kellam looked up at the raven sat atop an ancient astrolabe, “Do you know where Scoresby is? Bring him here if you can. I need his opinion.” Mrs Millward cocked her head to one side, seemed to ponder the request, and took flight. Leaving with a restrained kraw.

Mrs Millward, unknown to anyone, was the first of the inhabitants of Innsmouth to see the aftermath of the Event. Flying high, she could see the town of Innsmouth in the distance, looking much as it had always done.

But behind, where Massachusetts once was, now the land was a perfect curving shore. Innsmouth, now an island with an arc of coastline so perfectly formed as to defy rational thought. Fields, woods, even some buildings were bisected by this curve.

Mrs Millward thought of the rookery that occupied a tall stand of elms by the dairy. Those elms had vanished. She assumed the rooks would have survived, and were now just looking out across the sea somewhere. She’d miss them. Excitable idiots, but they reminded her of her youth.

Scoresby had been in town during the event, and upon waking, he’d hurried back to his cottage by the abbey to collect his instruments. Just before the … thing, the sphere, had overtaken the town, he’d seen St Elmo’s Fire dancing across the ships’ rigging by the quay.

Was that still measurable? Had it left a mark on the fabric of the town? On the structures, perhaps even in the memory of the stone and wood and metal itself? This was science at last. Something unique to study and contemplate.

Mrs Millward landed on the fence surrounding Scoresby’s cottage, just as Scoresby was closing the door. Laden with bags, satchels, canvas containers, and an arm full of journals, Scoresby looked up, startled slightly, by the large jet black bird.

Scoresby looked at the Raven. “Yes?” He asked. The Raven let out a ‘kronk’, and a series of quieter skawks, chirps, and tocs. Scoresby sighed. “I can’t come now. He’ll have to come to me. Advise your master to meet me at The Rock.”

Now Mrs Millward seemed to sigh. “Humans.” she thought tiredly. Nevertheless, she launched herself upwards, and retraced her route back to the observatory, informing Midwinter to gather his workings and head for The Rock, that black mass of iron that split Innsmouth in two.

Twenty five minutes later…

“Scoresby!” Kellam Midwinter rushed to his friend standing by the quayside. “Thank God you’re OK.” The men clasped arms. “I am. Are you? Does the observatory still stand?” Looking around at the toppled buildings across the town.

“I’m fine. Thank you. But, there’s something you must see!” Midwinter cast down his bags and pressed a notebook under Scoresby’s nose. “Look! We aren’t in Winter anymore!” He looked at his friend, waiting for understanding to dawn.

“What do you mean?” said Scoresby, his friend looked wild, “Of course it’s winter. Did you bang your head?” Kellam replied urgently, “The charts! The stars! Nothing’s in the right place William. We’re in Spring! Or at least the heavens are.”

Scoresby was an intelligent man, and what his friend was telling him was impossible, and yet… He looked around, the sun did seem higher than it should, and the breeze off the ocean, definitely warmer than usual for late December.

Looking back at his friend, Scoresby could see the certainty in his eyes. He’d come to trust Kellam completely over the last few years, and he trusted him now.

“But how?” Scoresby asked?

“I have absolutely no idea.” said Midwinter. He put his hand on Scoresby’s shoulder, “But let’s be honest, it’s far from the strangest thing that this town has seen.”

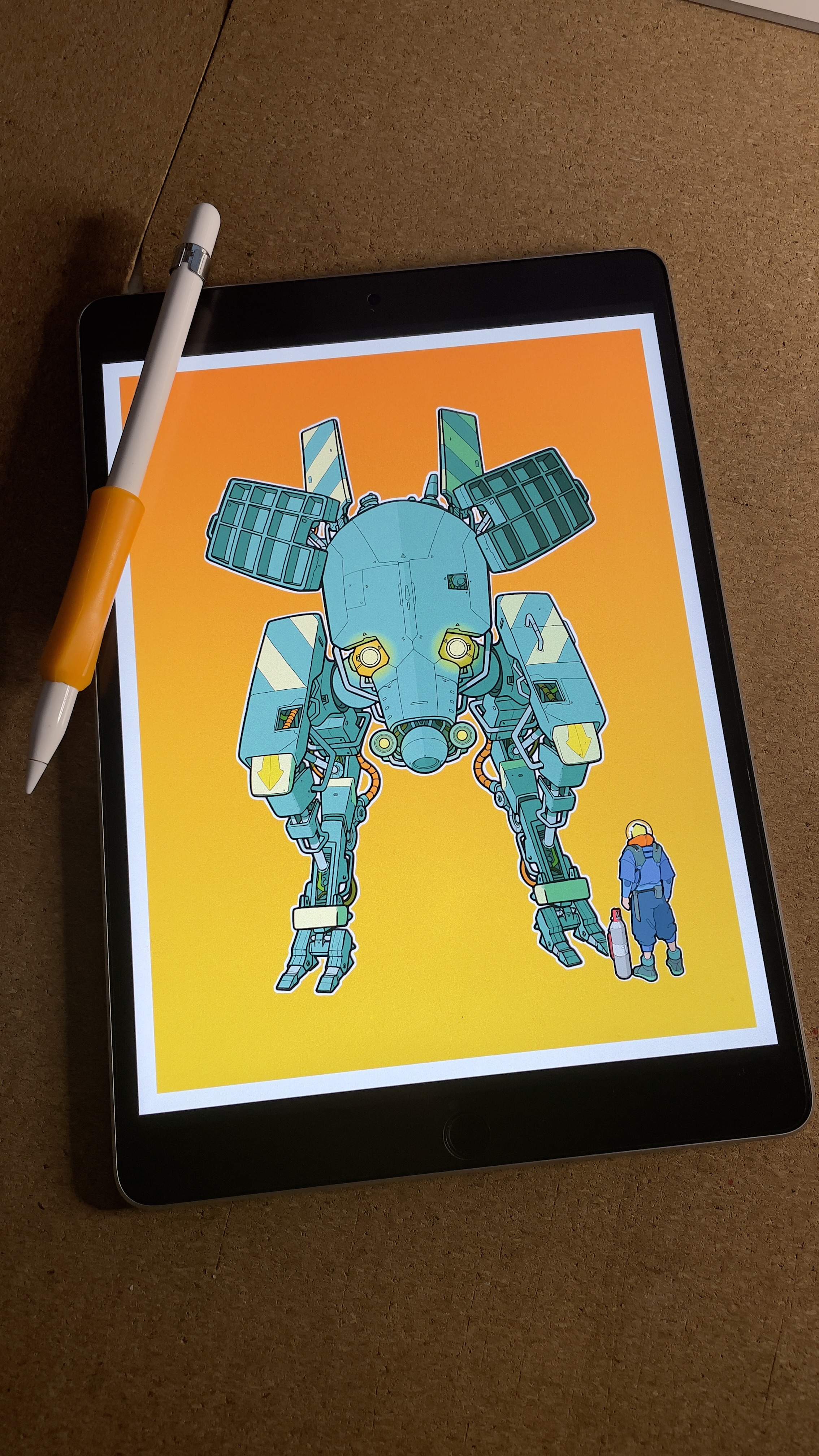

Degorius Priest, Keeper of the Reefs, watched the two scientists talking animatedly, as he pushed his clinker-built row boat from the quayside. Sat with him, was Truelove Brewster, weighing down one end of the craft in his home-made bathysuit.

Brewster was a newcomer to Innsmouth, having lived in the town for just 23 years. He came as a ships mate aboard a Royal Navy scientific vessel, staying behind (unintentionally) when the ship sailed for South America to observe a transit of Venus.

Now in his late thirties, Truelove is the town’s inventor and engineer. He’s also the only person brave enough to search the ocean bed for sky iron, which he does using his bathysuit.

Priest and Brewster had decided the scene of The Event, should be investigated. Degorius knew the reefs better than anyone, and only Truelove had the means to explore the depths where the creature appeared twice a year.

As the pair approached the reef, where the creature died and The Event was centred, they could see someone else already there. A similar rowing boat moored at the rock jetty built by Degorius himself.

John Winspear, originally from Hartlepool, took a rope from Priest, and looped it around the iron bitt that had been attached to the stone.

“Afternoon lads. You’ve had the same thought as me by the looks of you.”

“Aye. Looks that way.” Degorius replied.

“Truelove’s going to have a look below, see what’s what.”

Priest and Winspear were good friends, and worked together sometimes to map the reefs and shoals.

Brewster was more wary of the Hartlepool man, coming from Darlington himself. Many years and thousands of miles of ocean don’t calm some rivalries.

Priest and Winspear worked together, arranging the ropes and sounding weights. Brewster attended to his bathysuit. He unloaded a small clockwork pump and attached to it leathery hoses that ran around a drum and on to the suit.

The helmet of the suit was heavy, made of iron with a lead crystal face plate bolted securely in place. Air was supplied to the helmet via the pump which remained at the surface. With this equipment Brewster had managed to dive to a depth of 35 fathoms.

“I’m ready when you are Degorius.” Truelove stood at the edge of the reef, where it quickly dropped away in to deeper water. Degorius made his way across the broken top of the reef which was littered with rope, timber, and the remnants of a thousand ship wrecks.

Degorius set down a winch a few feet from where Truelove stood in his cumbersome suit, and attached the thick rope to the harness that ran around the waist, shoulders and thighs. Brewster was now attached to the reef by 40 fathoms of rope, and 45 fathoms of air hose.

“Set?” Said Degorius. “Aye.” Brewster nodded, and with that stepped off the edge of the reef. For a few yards, it was like Truelove was simply walking down some steps in to the sea, and then, one last step and he sank almost instantly below the surface.

The winch spun freely for a moment, before the cork sewn in to various pockets of the suits did their job and slowed Brewsters plunge. Degorius adjusted the winch, slowing it further, and checked on the clockwork pump. All was well for now.

A thin line ran freely through the glove on Degorius’s right hand. Too insubstantial for safety purposes, it existed as a means for Truelove to signal to the surface if he encountered trouble, or for when he wanted the winch reversing to assist his ascent.

Under the surface, Truelove Brewster descended. At first, he was accompanied by the pops and clicks of the reef. Fish and crustaceans, sponges and corals, all with their own sounds. As he fell deeper, the only noise was his breathing and the hiss of the pump.

As the gloom deepened, Truelove activated a lamp on the top of his helmet. Phosphorescent minerals, which had been subjected to intense refracted sunlight for days in advance, glowed bright green within the lamp chamber. Everything was immediately cast in a sickly light.

The reef stood in very deep water. It was this that made Innsmouth such a good port – deep harbours for ships belly-full of whale blubber or cod. There was a current, welling up from the depths. Cold, nutrient rich water, chilling Brewster despite the thick, oiled suit he wore.

Ahead of him in the gloom as he sank, the reef seemed to curve away from Truelove. Was there an overhang? Within seconds the reef had receded so far it was beyond Brewster’s sight. He tugged twice hard on the rope, and almost immediately the winch hauled him to a stop.

He hung almost motionless in the water. The markings on the rope indicated he was at just fifteen fathoms, ninety feet. The current swelled against him, gently lifting Truelove before letting him go in a predictable cycle. Ahead of him. Nothing.

The reef in front of him had vanished. It was still visible, just, as a shadow above. But ahead, in that grim, green glow, nothing but the flickering of small shoals of small fish. Brewster waved hims arms, propelling himself forward a little. Was there… something… there?

Truelove Brewster squinted through the green gloom, and the green gloom moved. There was a shifting of something. Like viewing the world through a cheap kaleidoscope. Fragments drifted in and out of focus. Shapes appeared and disappeared. And the ocean grew colder.

His heart began to race, and Truelove’s breathing grew faster. In him a fear appeared. A terror. Something deep inside him was horrified at the the movement in the ocean in front of him. He hung from the rope, too afraid to move.

In the darkness, a thick, barnacled tentacle appeared. As thick as a tree trunk, it probed the darkness towards the terrified Brewster. As it grew closer, it seemed to slip out of sight, appearing again in a slightly different place.

Truelove understood that by seeing it, he was somehow triggering this shift. And then, suddenly, it was right in front of him, the tip of that tentacle just inches from the faceplate of the bathysuit. It shimmered in the gloom, like oil on water.

Beyond the tentacle, nothing could be seen, but Brewster could sense an enormous presence. Something unfathomably vast, just out of sight or sensation. There was an ancient coldness, permeating the water, something icier than the bitterest winter night at sea.

His mind lost all clarity as he hung there. A blankness gnawing at his memory. He couldn’t move. Forgetting what movement was. Forgetting his own name. Forgetting what he was. His breath grew shallow and slow. The cold thickening his blood until his heart strained to move it.

The tentacle moved towards him, just as Truelove’s sight narrowed, blackness crawling from the edges of his sight. Everything grew silent. No longer could he hear his breathing, or the whine and clicks of the air pump. Everything grew still. The swell of the current even paused.

Then, just as everything seemed about to wink out of existence for poor Truelove Brewster, he was hauled upward. The tentacles writhed and retracted, disappearing in a shattering of shadows.

The cold receded quickly as Truelove ascended, his heartbeat drumming in his ears nearly drowning out the sound of his breathing. The ocean grew brighter, and life reappeared as the reef and its inhabitants came in to view.

Brewster detached the cork belt as he rose, wanting nothing to slow his return to the surface. He couldn’t look up in the bulky suit, but he could sense his depth accurately, five fathoms, four, three, two, one…

He breached the surface in a miniature maelstrom of bubbles and reached his arms up to find, thankfully, Degorius Priest and John Winspear grabbing at him and his harness, and pulling him to the shallows.

Truelove laid on his back on the jagged reef, gasping for breath and allowing his heart to stop pounding. So loud was the blood racing in his ears, he couldn’t hear a word his companions were saying.

After a moment, his breathing almost normal, and the warmth reaching his fingers and toes, Brewster opened his eyes. His friends, for surely he would count Winspear as a friend now, were silhouetted against a bright, full moon shining in a sky brim-full of stars.

Truelove stared at the moon as his helmet was unlatched and removed. It was early afternoon when he started his dive. He’d only been gone twenty minutes or so. Surely? Or had he passed out, down there in the depths. He shivered, remembering the cold, and that ‘thing’.

“Brewster!” Degorius leant over him and bellowed, “Can you hear me man?” “Yes. Yes. What time is it? How long was I gone?” Truelove sat up and, with the help of the two men, shrugged off his harness. He couldn’t stop staring at the moon.

Priest and Winspear looked at each other. Concern and confusion in equal measure. “You’ve been gone thirty hours man. Thirty hours. We thought we’d lost you. The winch reached the end of its measure and we couldn’t haul you back up.”.

Thirty hours? Brewster couldn’t believe it. It had only been minutes for him. He looked up again at the moon, bright where the sun should be. “Degorius went back to town to get help. Young Clarence dived down to try and find you, but you were too deep and the current too strong.”

Turning his head, he suddenly noticed a knot of men standing close by. All fishers and whalers he knew well. Clarence Bulkington sat among them, hair still damp.

Clarence nodded, acknowledging Truelove’s obvious gratitude. “What happened down there Brewster? What happened to you? Your hair…” Winspear touch the top of Brewster’s head as his words trailed off. “Your hair’s bright white my friend.” said Degorius gently.

Truelove didn’t speak on the trip back to shore. He sat against the gunwale of John Winspear’s rowing boat, two thick blankets wrapped around him. He toyed with the fringe of hair long enough to see. It shone in the moonlight. Not grey, but bright white as Priest had said.

On land, the group of men made their way quietly, straight to the Inn on the Rock, filing through its door in to the warm glow of a roaring fire and a multitude of whale oil lanterns. Rose Gryvill, proprietor of the inn, rushed over and fussed Brewster to a seat by the fire.

As Truelove was warmed and fed, and many of the other men stood about talking, Degorius Priest and John Winspear stood in a corner of the inn with Bartholomew Gosnold. They spoke quietly, just as Jack Keane struck up a mournful ballad on the old upright piano.

“What happened out there?”, Gosnold was stony-faced and serious, concern read easily on his brow. “Brewster went down as normal, at 15 fathoms, he pulled the line for us to halt his descent. Then nothing for almost an hour. We tugged the line and didn’t get a response.”

Winspear took off where Degorius had paused. “We tried the winch, but it just wouldn’t haul him up. We didn’t want to force it in case it broke. Then, all of a sudden, the line, the winch, the air house, all ran right out. Over forty fathoms in a matter of seconds.”

“Forty? That’s too deep? Too deep to survive.” Gosnold stared at the men, wanting an explanation he could understand.“Well, it’s deeper than anyone’s been before, that’s for sure. But there he is…” Degorius nodded in the direction of Brewster, “Alive, if not alive and well.”

“He claims he was only under water for twenty minutes or so, and went no deeper than fifteen fathoms. He’s said no more than that so far.” Winspear was as troubled as the whaler. “And his hair?” asked Gosnold.

“Well, there’s almost thirty hours and at least twenty five fathoms to account for. I reckon that might explain his hair. The doc’s on his way now to have a look at him.” Degorius paused, “There is one more thing…”

“John here, he took soundings around the reef. All the way around. Usually it’s around ten fathoms deep there, roughly, before dropping to thirty five at the sea bed.” Priest looked to Winspear to confirm this fact.

“Aye. We map the reef and measure the depths after every storm. Just in case anything’s shifted and we have to amend the charts.” said Winspear. “And now?” asked Gosnold, obviously expecting another revelation.

“I ran out of line.” Said John Winspear. “Nowhere around the reef could I find the bottom. Sixty five fathoms of line, and I couldn’t find the sea bed.”

*

The following morning, Humility Cooper, owner of Leviathan, was at sea. Humility was married in to the fisherfolk, and won their trust by capturing a sea serpent single-handed. Shorter than most, she has hair that curls when the seas are high and freckles that itch when mackerel are shoaling.

Humility, and Leviathan – a short and stout boat painted in dazzle camouflage, were fifteen miles west of Innsmouth, having rounded, what was now, the island. Many Innsmouth folk were seen along the new coastline, gathered in groups discussing this new state of affairs.

Humility had marvelled, in a mixture of fear and awe, at the perfect curve of cliffs that now truncated the land where once the rest of Massachusetts had been.

Waterfalls dropped straight in to the ocean where rivers had once been. Buildings perched precariously, some not yet decided whether to stay or fall in to the sea. A cow sat, confused, on a slab of pasture that had slipped hallway down a cliff.

Having passed beyond the island, Humility and Leviathan were in open ocean. No sign of land could be seen. The sea was weirdly, unnaturally calm. Its surface glassy and oily, moving in thick, slow swirls, lapping at the sides of the boat in a curious way, lazy and echoless.

The thing that struck Humility the most, was the silence. She shut off Leviathan’s engine and allowed the boat to just coast.

There was barely a noise. No gulls or terns following the wake. No gannets spearing the ocean in a flash of yellow and bright white. The ocean surface was entirely undisturbed by fish, large or small.

As Leviathan paused, Humility sat on the starboard gunwale and sipped strong, bitter coffee from a flask. She stared down at the sea. Sunbeams pierced the stillness, disappearing in to the, seemingly, infinite depths.

After a few minutes of calm, a shape appeared in the deep, as it rose it resolved in to two separate masses, one much larger than the other. A female Wright whale and a calf.

The mother almost fifty feet long, with the typical pale-patched nose of the species, barnacles and whale-lice in abundance.

The calf, only a quarter the size of the parent, its nose less parasitized, rose smoothly to the surface, and broke water just an arm’s length from Humility. She reached out, leaning and bracing herself against an iron deck cleat, her hand just inches from the young whale.

Slowly, the calf drifted closer, its mother ascending to shepherd it, but staying just below the surface. Humility reached further, and placed her hand on the nose of the whale. It pressed upward and she rubbed its snout.

Humility’s blissful moment was short lived. The deep water beneath the whales shifted. A dark mass slipped through the faltering sunbeams just as the sun passed behind a cloud. Humility shivered. Whatever that was, it was huge, much, much bigger than the whales.

The whales sensed something too. The mother nudging the calf away from the boat and swimming powerfully away with a languid swish of her fluke. The calf turned to follow, Humility seeing her own silhouette reflected in its dark eye.

The sea erupted and Humility was thrown back across the boat, landing hard on her back over the hatch. Leviathan rocked wildly as the air turned black. The Wright whale calf, thrust in to the sky trapped between the huge, ugly jaws of a gigantic creature.

Its size was bewildering, as it seemed to take an age to complete its leap. The body, black, glistening, oily and rippled, pocked with strange scars, carved a dark arc in reality.

As the creature plunged back below the surface, the air was left thick with salt spray, whale blood, and the stench of the its breath.

The ship rocked, and rocked less as the sea calmed. The sun returned from behind the clouds. It was almost as if nothing had happened. Though that thought was quickly banished – Humility and her boat were coated in a mist of blood.

Propped up on her elbows, as she gathered her breath and her heart stopped pounding, Humility gazed at the plaque on the wheelhouse. It read, simply ‘The Leviathan’. Ship and creature, twinned in name. Just a coincidence she told herself.

After changing her vest and overshirt, and putting on a clean cap, Humility sluiced down the deck of The Leviathan as best she could. Standing in the wheelhouse, another coffee in her hand, she was about to turn the boat around and head for home.

Her hands firmly on the wheel, Humility was stopped by something on the horizon. Land! It was just at the furthest reaches of her vision, but it was definitely land. She checked her charts on the desk beside her. She was Almost thirty miles due West of the ‘island’ of Innsmouth now.

The island part of that was going to take some getting used to. Previously, 30 miles west of Innsmouth was the town of Medfield, deep in the Massachusetts countryside. Humility had been there a couple of times on family business. Business she was glad was now over.

The Leviathan surged forward as Humility pushed the throttle fully forward. It was reassuring to have some noise again, the silence before and after the creature‘s brief appearance had been unnerving.

The ships binoculars had broken, falling from the desk and cracking, during the attack, so Humility was reliant on her eyes as she approached land. She leaned forward over the wheel, straining to pick out details.

The first thing she made out as she approached, were the three lighthouses, strung out across several miles of ocean. Just like Innsmouth’s lights. Weird. She’d never heard of another town with a similar arrangement. Closer still, and Humility was getting a very bad feeling.

Three lighthouses. A harbour. A town at the base of a cliff. A church on the highest point of the land. Just like Innsmouth. Three or four miles out and she was sure. This was Innsmouth. But somehow, nearly forty miles west of where it should be.

The Leviathan had sailed due west of Innsmouth, now it approached it from the East, as if Humility and her ship had circumnavigated some tiny world completely. Assuming this was Innsmouth of course. Not some strange doppelgänger.

Humility piloted her boat in to the harbour, left of The Rock that divided the town, where the fisherfolk docked. As The Leviathan pulled in, Moses Fletcher – owner of the Low Ebb, and a good friend of Humility, stood on the quayside.

“I beat you back by twenty minutes Cooper.” Fletcher shouted down to Humility as he caught and tied off the hawser she’d thrown him. He noticed the strained look on her face immediately. “Got turned around out there did you? Like me?”.

Moses Fletcher was an experienced seaman and had fished out of Innsmouth for nearly thirty years. He didn’t just get turned around. He must have had the same experience as Humility.

What in the name of the Sealamb was going on?

*

That afternoon, Moses and Humility compared tales at a table in The Inn on the Rock, and a meeting took place between Gosnold, White, Priest, Scorsesby and Midwinter in the back of Tempest Dunn’s bookshop. There was, obviously, much to discuss.

At the same time, it occurred to Robert Coppin – owner of the Pelagic – that someone should probably check on the inhabitant of the South Light, the most distant of Innsmouth’s lighthouses.

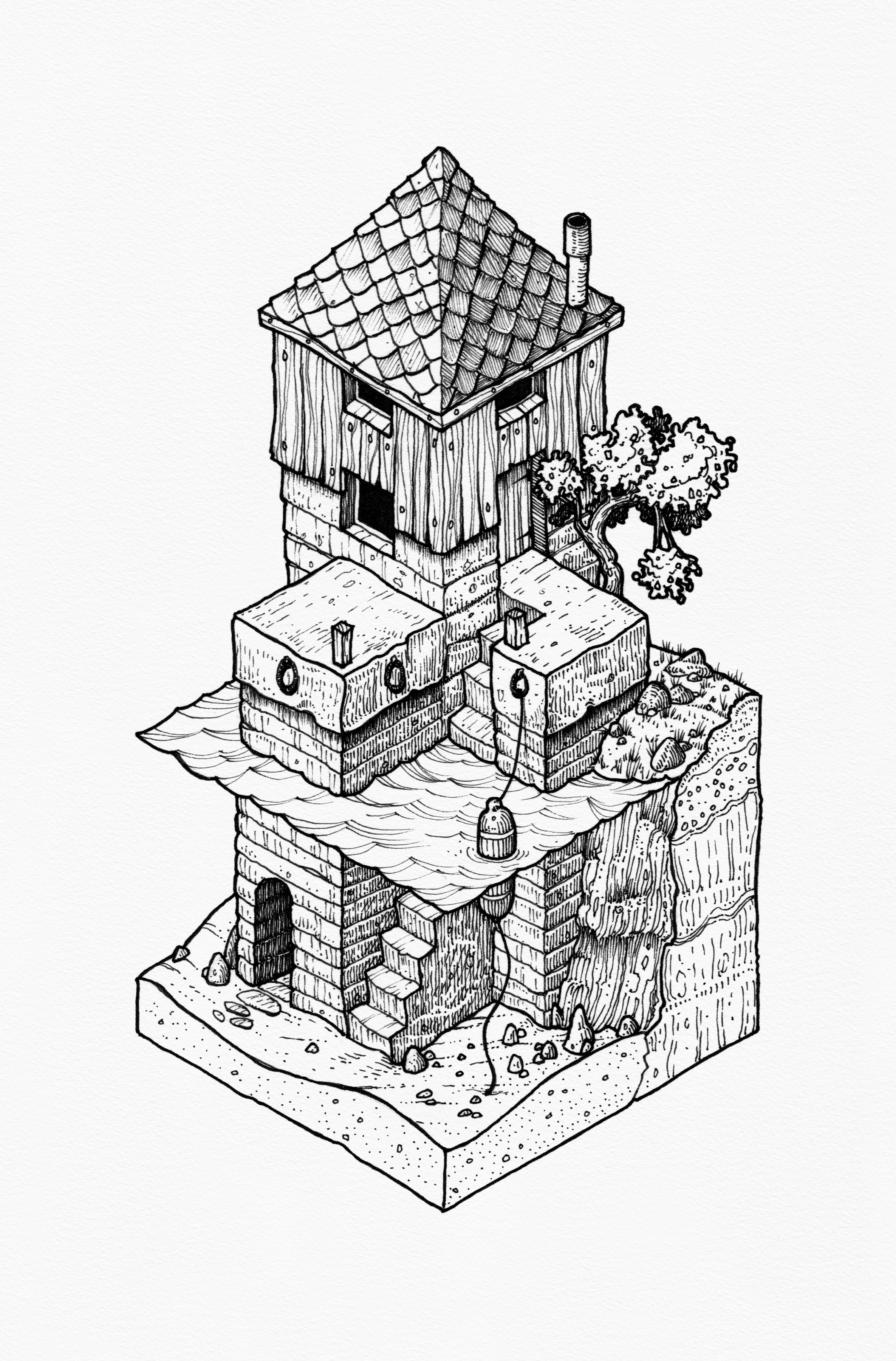

The South Light was also Innsmouth’s newest lighthouse, built less than four score years since. John Crackstone mans the lamp, and always has. John fled Essex as a young boy, hounded out of England by those who opposed his father’s, rather eccentric, religious views.

Finding himself in New England more by luck than design, John managed to secure an apprenticeship with the clerk of works at the marine engineers of New Bedford. He soon proved himself a more than capable draftsmen, and found work with Mr Winstanley – lighthouse architect.

When Winstanley hung up his pen and dividers, John Crackstone was entrusted to design and oversee the building of the South Light at Innsmouth. Personally attending to every detail, once it was finished, Crackstone bricked himself in to the tower and never left.

The house at the base of the lighthouse serves only as a store, and somewhere to wait out the weather for those that provision the tower by means of a winch and pulley system. How they’ll get John out when his days are up nobody knows.

Coppin left the Pelagic at anchor, and borrowed a small tender from a friend. He headed out of the port, skirting between the harbour wall and The Pins – Four rocks guarding the waters of Innsmouth.

Standing a few hundred yards off the seafront, they were connected long ago by a seawall of slate and granite – offering protection from the worst of the winter storms.

At one end of The Pins a small house stood, occupied for the last forty years by James Arnold – a once successful businessman of New England, now fallen on the hardest of times. Exiled by both his family, and by Boston society, he was heard or seen little in Innsmouth these days.

Coppin sailed south on leaving the harbour, and made, by eye, for the lighthouse that stood two miles off shore. The sea was calm, and no birds marked the pale blue sky. The only sound was the gentle put-put-put of the boat’s engine.

As Robert approached the mass of rock and reef upon which the light stood, he was reassured to see it looked undamaged by the event. The tower reached 75 feet in to the sky, including the lantern and copper roof. The doorway was perched, strangely, one third of the way up.

Crackstone has simply decided, when designing the structure, that it was easier to build the entrance above the worst of the waves, and access it by ladders. This was all very well if you had a ladder. Robert Coppin did not have a ladder.

Mooring the tender at the rocky quay, just beyond the wreck of an old two-masted ship that had run aground a decade ago, Robert Coppin set foot on the South Light. Shipwrecks at the base of lighthouses are never a good thing he thought as he approached the store house.

Crackstone was taken ill rarely, and just once had his illness prevented him for keeping the light lit. Sadly that one night coincided with a storm, and an inexperienced captain, resulting in the wrecking of the schooner USS Grampus.

The store house was locked, but the key – large and made of iron – hung from a hook next to the door. There was no concern for burglars out here, but other things sometimes tried to explore. Coppin unhooked the key, unlocked the door and swung it open.

The stench hit him like a punch. He reeled back and tripped over a coil of rope. He could almost see the odour rippling across the threshold towards him from the darkness. He stood, covering his mouth and nose with his sleeve, and backed away.

The smell was astonishing. A rich and bitter mix of rotten eggs and fetid meat, with a bit of vinegary beer for good measure. Coppin peered in to the gloom, and flicked the light switch.

The contents of the store, normally well ordered and sorted on shelves, were a chaos of mould on the floor. Everything had rotted down to one gelatinous mass. In some places thick, pale green, fur had established itself like a lurid blanket.

In other places, pustules erupted in tiny clouds of spores, swirling in the air before seeming to reach towards Robert. He stepped back, having seen enough of that, and slammed the door shut. Taking a deep breath of fresh sea air, he made for the lighthouse itself.

Standing at the base of the light, it’s cream-coloured, rough-rendered walls reaching up to the sky, Coppin shouted for the keeper. “John! John Crackstone! Are you there man?”. He repeated his his call twice more, before remembering the bell.

A rope ran down from a hole in the wall, just below the lantern. Iron rings guided it to ground level, where a large hagstone was tied to it. Robert gave the rope a tug, and heard the ‘cl’ of a bell clanging before the rope snapped and fell in a mess at his feet.

“Neptune’s teeth!” Cursed Coppin.

He walked back around to the front of the lighthouse, and gazed up to the lantern. Everything seemed intact up there. The thick glass around the light, the iron railings painted a bright orange, the copper roof. “John Crackstone!” where the sodden hell is he thought Robert.

And then, he appeared. The door, built in to the lantern itself, hinged inward and John Crackstone shuffled forward in to view. John had lived in the lighthouse since it was built, and had apparently spent a good twenty years before that learning his trade. Which must make him…

Well, at least a hundred and ten years old. If not more. He looked every day of that too. He wore a faded, grey flannel shirt, and grey dungarees, with a grey woollen hat perched on the top of his head. His skin, pale, thin, stretched like a dried leaf, was similarly grey.

Crackstone’s hair, for variety’s sake, was bright white.

You’d have no trouble imagining Crackstone was long dead, simply haunting the South Light. His soul refusing to leave just like he’d refused to leave it in life. Coppin shivered. Surely not? That was actually John up there. Wasn’t it?

“What do you want?” Crackstone seemed to whisper the words, but they reached Coppin easily enough, unhindered by the breeze and the waves. His voice sounded hollow, deeper than Robert had remembered. Like an old baritone.

“I came to see if you were safe John. Came to see if you needed anything. After the…”, Coppin pointed back towards Innsmouth, and waved his hand vaguely, “after the thing that happened.”

Crackstone followed Robert’s finger, and slowly turned his head towards town. It seemed an age before he replied.“That was a dark thing they did Robert. Traditions are meant to last.”

Coppin sighed. “Aye John. But the kids. How many kids have we lost to that beast? Hundreds. It had to end sometime.” Crackstone grasped the railing and stared down towards his visitor. The ironwork creaked.

“Children.” Crackstone sneered the words out. “Children. There are always plenty of children, Coppin. There’s no shortage of youth in this world. Just the opposite. Too much noise. Too much… vitality. All that energy, it’s wasted on them.”

Robert sighed. John had always been a grumpy old bugger, and in recent years he’d become more unpredictable. “Youcan’t mean that John? It’s a blessing we’re free of that now. It hung over this town far too long.”

“Too long? You know nothing of too long Robert. Eighty years in this tower, and that’s nothing. The blink of an eye. You don’t know how long some have waited.” And with that, John Crackstone stepped backwards in to the lantern, and closed the door behind him.

Well, that went well, thought Coppin. He looked around, for inspiration as much for anything specific. Nothing sprung to mind. Crackstone was, if not well, at least healthy enough to man the light. He didn’t seem to need anything. So that was that.

Coppin would come back in a few days with some help to clean out the store house and reprovision it. Somehow the bell needed fixing too, but there was no way to do that without Crackstone’s help.

Robert looked back at the lighthouse as he steered away in the tender. There was no sign of Crackstone, and nothing looked amiss with the lighthouse. Coppin was already thinking of an ale in the Inn, and a plate of hot stew. Something to take his mind off this strange day.

In the lantern, Coppin’s retreat was observed, not by John Crackstone, but by something far more ancient. The lighthouse keeper stood in the lantern, as still as bone. His eyes, glassy and clouded like opals.

Crackstone had been dead for two days now.

Behind him, almost filling the space around the light, a huge glistening tentacle writhed slowly. Slipping over and around itself, making the strangest, sickly, rasping sound, it ended in a thinner tendril, that pierced Crackstone’s neck at the base of his skull.

The tendril pulsed, and Crackstone moved slowly back and in to a chair, slumping like a marionette whose strings had been cut, as the creature released him.

The tentacle slipped from the lantern, disappearing down the stone stairs, through the store, leaving broken bulbs and filaments behind. Down through Crackstone’s bedroom, coating the walls with iridescent mucus.

Down through the kitchen, past food rotted by its very existence. Down more stone steps, to the living quarters and office. Charts, and plotters, maps and dividers, brushed from desks on to the floor coated with inches of putrid slime.

When the tendril reached the base of the lighthouse, it seemed to shimmer and shift, flickering in and out of sight. It retreated through solid rock. The whole building vibrated as the creature slipped away, back below the stone, towards the depths.

All was still on the South Light. Only a stench remained.

*

Behind the harbour, Innsmouth’s buildings crept gently uphill, before coming to a halt at the foot of a crescent of cliffs that surrounded the town. Atop the cliffs, reached by a winding path, the old abbey. Fallen in to ruin now.

Somewhere in those inclined streets, was the doctor’s surgery, presided over by William Wickinson. A smart stone-built house, among less permanent looking residences, the surgery was white-fronted, with a red-striped painted narwhal’s tusk above the door.

Wickinson himself, a Boston man, 70 years old and thin as a walking stick, has been the town’s doctor for nearly fifty years. Treating all ailments, sicknesses, setting broken bones, and assisting the midwives of Innsmouth (there are always two, a fisher and a whaler).

The doctor has an extensive library, and over the years he’s cultivated a good friendship with Tempest Dunn the bookbinder. Wickinson also has a huge collection of gramophone records but, alas, nothing to play them on.

His assistant, in all things curative, is Elizabeth Unger, an orphaned whaler girl. Her father died of the pox some years ago, and Wickinson took her in, first as a help, then to aid with filing and record keeping. Now she’s almost as able in medical matters as the good doctor.

Today, the doctor was attending to Chester and Clarence Bulkington. Twins, they lived, worked, and went everywhere together. That included, both falling when part of the whaler’s quay collapsed during the ‘event’.

Chester had fallen on to a lower part of the dock, cracking his head. The doctor had stitched that up quickly a couple of days ago. Clarence had fallen straight in to the sea, and nobody was quite sure how long he was submerged before being pulled to shore.

It was Clarence that was the patient today. There were no recognisable issues to deal with that one would normally associate with a near drowning. No cough, no chest pains, no dizziness. Clarence’s breathing, eyesight, and hearing seemed normal.

But, the young man’s appearance, well, that was not normal. The twins were whalers. And typical of their brethren, they were dark-haired, stocky, hirsute young men. Chester’s head was covered in a mop of unruly, jet black curls, and a full beard clung to his face.

Clarence, had been identical. A couple of days ago, you would have struggled to tell the men apart.

The younger brother, by just one minute, was visibly paler skinned now. And his dermis seemed almost translucent, veins and arteries tracing blue and red pathways along his arms. The texture too was different, wrong. Waxy, it left a residue on the doctors fingertips.

Clarence’s hair was falling out. Already much thinner than Chester’s and lacklustre, clinging lifelessly to his scalp. His beard too, more threadbare, and with a distinct smattering of white. Clarence looked a good (or bad) ten years older than his brother.

“How do you feel Clarence?” Asked Wickinson as he listened to the man’s chest, a heartbeat hard to find so faint it was.“Tired really doc. Just tired.” The words came out like a series of sighs. He looked completely exhausted thought the doctor.*

“Take off your shirt Clarence, let’s have a proper look at you.” The doctor rolled up his sleeves, as Clarence, aided by his brother shrugged off his shirt of dark brown twill. His chest was sunken, his ribs protruding. The skin on his body as diaphanous as that on his arms.

The doctor sighed. Clarence looked like a consumptive patient, or someone suffering a long period of blood infection, or perhaps an addict of some kind. He did not look like a healthy young man who had simply fallen in to the ocean.

Wickinson examined Clarence as well as he could. Taking his temperature, blood pressure, measuring his pulse. He took samples of hair and skin, and of the residue that covered the man’s body. There was a smell too, something slightly acrid and bitter.

When the doctor examined Clarence’s eyes, shining a bright light in to each pupil in turn, the doctor thought he could see something moving within. Perhaps the retina had been damaged in the fall? Or, Lamb forbid, a parasite of some sort?

Wickinson made up a solution containing a Mercuric compound. It was normally given to sheep to treat worm infections, but it was all the doctor had available. “Chester, make sure your brother takes two drops of this on his tongue every day for a week. Do not forget.”

“OK Clarence. I’m going to prescribe some vitamins for you to take daily. Don’t forget now. And you need to get plenty of iron. So go to the Inn, tell them I sent you, and have them make you up some of Rose’s stew. That should help. Now, I just need to take some more blood.”

Clarence barely registered was the doctor was saying, or at least gave no indication if he did. Wickinson drew a large phial of blood from the young man’s right arm. It filled the syringe thinly, like a tea unbrewed, weak and unsatisfying.

“Chester, make sure he does as I say now. I’ll do some tests. Come back the day after tomorrow.” Chester clothed his twin and led him by the arm out in to the street, clutching tightly the doctor’s prescription.

“Do you think he’ll be OK Doctor?” asked Elizabeth. She’d stood in the corner of the room as Wickinson had carried out his examination. She looked shaken by Clarence’s appearance.

“I have no idea Miss Unger. I really haven’t a clue what’s wrong with him. And how he’s taken such a turn in such a short space of time I don’t know.” Wickinson was scrawling furiously on a piece of paper which he put in a sturdy envelope with the blood sample.

He addressed it and handed it to Elizabeth. “Get this to the courier and have him deliver it to Bartlett at Plymouth Hospital. He may have a better idea than I.” Elizabeth didn’t move, and looked embarrassed. “Dammit!” The doctor rarely cursed.

He realised now that Plymouth Hospital may as well be the moon to the people of Innsmouth. “I’d better test that myself then.” Wickinson snatched the envelope back and retired to his study muttering to himself.

Elizabeth was scared. Scared for Clarence, for herself, the doctor. Scared for everyone. They were all alone now. She’d never feared the ocean before, but she did now. It felt oppressive and vast.

*

Printed matter:

The Innsmouth Ammonite is a gazette, part news, part gossip, items for sale, services available. Printed on a paper derived from kelp, the Ammonite is a pale sickly yellow in colour – giving it the nickname The Fluke Puke.

The Beast is Dead! But at what price?

Innsmouth an Island!

Mysterious illness strikes Fishers and Whalers alike.

Can you hear that hum?

Hen’s eggs in short supply – try lizard eggs instead!

Houlgrave’s Unguents

Harriot’s Chandlers – buying + selling now!

Bethlehem’s Boats are Best

South Light Stink!

The Beast is Dead! But at what price?

The beast is finally dead! Yog-Sothoth slain by the whalers’ harpoon! The winter solstice, so long a dark day in our town, has finally brought joy and release from the shackles of servitude that have weighed us down for so many generations. Since 1666 we’ve offered up our children, at the behest of our churches, to that fell creature from the depths. Those eyes, those sinuous limbs, all reaching, sucking our souls of light. Now we are free. No more shall we suffer the pain of sacrifice and the guilt and shame that accompanies it. The beast is dead.

But… at what price our freedom? All reports point to Innsmouth now being adrift in an endless ocean! No land has been sighted. No shipping has sailed to our rescue. We are alone it seems, more than ever perhaps. Strange sickness are afflicting townsfolk, fishers and whalers alike. Food rots in the fields and on the shelves. Birds are absent from our skies. Even the sea seems strangely desolate. Time will tell the toll we pay for our liberty. But for now, folk of Innsmouth, rejoice where you can. Hug your children. We have a new God and its name is hope.

*

Agnes Houlgrave sat in the dark. The evening was drawing in, and she’d lit no candles today to beat away the gloom. All was still in the dying light, even motes of dust seem to pause.

Agnes was old, some thought perhaps as old as anyone in Innsmouth – save perhaps for Crackstone. Her face was well lined. Lines upon lines. Each one with a story to tell, of mistakes made, roads travelled, lovers lost.

Her birth year forgotten long ago, although she remembered the date – November 11th. It was the same day, many years later she’d first set foot in Innsmouth as a young woman. Many asked what she was running from when she arrived, what wasn’t she running from she’d always reply.

Agnes had many tales to tell, but for now she was quiet, and she was ill at ease. She hadn’t ventured out on the solstice. Seeing two innocents sacrificed to that beast was nothing to be celebrated. The saddest of habits this town had acquired.

She’d stayed put, behind the counter of her tiny shop, mixing ingredients for some ointment or another. Something for every ailment she said. Rashes, headaches, the droop, bad luck, bad back, bad thoughts. Houlgrave could mend anything except a net.

When the creature died, out there on the black reef, Agnes had lost consciousness along with everyone else in the town. When she awoke, it was with a sore head and a bruised hip. The rough wooden boards of the floor beneath her.

Several jars had smashed when she fell, and when Agnes cleared up the mess, she noticed that the unguent she made from a bowhead whale was changing. The thick, opaque, creamy-white, salve was turning black, and beginning to bubble.

As Agnes looked closer, the ointment seemed to writhe like a worm just stepped upon. She’d never seen anything like it and wondered if it had been contaminated when it smashed.

Placing the broken jar on a plate, she covered it with a thick glass bell jar. Immediately the movement stopped. Agnes lifted the glass a little, and the substance moved once more. Curious.

The salve was mostly whale blubber, cod liver oil, and some herbs. It was boiled until all texture was absent, and it resembled the thickened cream of a goat. There was certainly no reason for it to move. Looking closer, apart from the colour, it looked normal again now.

Nothing else that had smashed showed any signs of change. None of those other jars contained any whale blubber, just vegetable oils and emulsions. Curious indeed.

Two days later, Agnes hadn’t yet left her shop. She’d ventured upstairs to her rooms, a simple bedroom that doubled as her parlour, and a bathroom that had a window that looked out across the jumble of roofs that made up the Whalers side of town.

She’d learned of what had occurred on midwinter’s day from townsfolk walking by, gossiping and exchanging their silly little opinions as they passed. The news of the children’s survival had warmed her heart more than anything in many a year.

Nobody had come to check on her. Not Gosnold, the head of the Whalers. Not the Cleric, head of the Church of the Harpoons. Nobody. She could be dead for all the people of Innsmouth knew. Perhaps things would be better that way.

Agnes looked at the index finger on her right hand, at the small cut she’d received when clearing the broken glass. It pulsed and oozed black blood, thick like tar. It hurt all the way up her arm, in to the pit where something swelled and throbbed. A cold sweat prickled her brow.

She cleaned the finger again, as best she could with distilled water and pickling vinegar, and wrapped it in a cotton bandage. Perhaps she should venture out and visit the doctor. She’d not normally bother him for anything, but this seemed anything but normal.

Agnes sighed and closed her eyes. Her sleep was troubled with strange dreams. Vast spaces, populated by creatures vaster still. Dimensions confused and turned inside out. Echoes of her own screams reached her before she’d even opened her mouth.

She awoke in complete darkness, and knew instantly she was no longer in her little shop.

Chapter Three.

That night, a still night, the fog swept slowly across the town of Innsmouth, and embraced it like a shroud. The lapping of the waves, the creaking of the wharf, footsteps of those rushing home to the warmth, all muffled like a funereal drum.

Some people stayed out in the mist, either not yet ready to let go of the day, or keen to make use of the veil of obscurity the fog provided.

One such person was Dr William Bateson. Not a ‘real’ doctor, not that he ever let the townsfolk know that, he specialised in biology, anatomy, and genetics, something he had studied in Leipzig, alongside other followers of Galton’s work.

Bateson, originally from Connecticut, had travelled widely across America and Europe, and had made the professional acquaintance of many varied scholars, scientists, and philosophers.

The, somewhat new, field of genetics and improvement, had interested him immediately with its infinite possibilities, and he sought out like-minded souls.

It quickly became evident to Bateson, that although many shared his views on these matters, few of his contemporaries had the desire to explore at any pace. William was impatient and swiftly moved on, seeking the more fringe members in the field.

After a decade in Europe, Bateson found his way back to the East coast of the United States. First, back in his home town of New Haven, before moving north and east through Rhode Island and in to Massachusetts.

Boston was his home for a while, before an unfortunate episode involving a mortuary and some missing cadavers forced him to move on. He’d been settled in Innsmouth for three years now, with lodgings west of The Rock, and a workshop east of The Rock.

It was from his workshop he’d come this evening, in to the fog, along the harbour side past the Whaler’s factory buildings, between those plants that processed the blubber and rendered the whale oil for transport. Through dark streets littered with the means of whaling.

He hurried past the Pearl and Oyster, not wanting to give in to the temptations it held. Turning right, he strode uphill before turning right once more in to a series of alleyways. The mist always with him like a silent companion.

Either side, high, narrow houses leaned in towards each other, close enough for neighbours to shake hands across the street. This part of town was claustrophobic on the brightest of days. Tonight it felt like a straight jacket to William.

He paused, cursing genetics that left him short of breath after such a brief walk. Looking around he assured himself he was in the right place, then he waited. He was early, as he always was. He slunk back in to the shadows, thankful for the mist and the cover it bestowed.

There was little stirring in the town now. It was cold and the atmosphere was oppressive. Something about this mist. It chilled to the bone, and then some more. He could hear children, in some high up room, laughing. An incongruous sound tonight.

At last, he sensed movement in the alleyway.

He focussed ahead and saw a human shape form out of the gloom. The sound of the cart he pulled behind him strangled like all other noises. “Doctor.” A statement from the man, rather than a question. He knew very well who he was.

“Good evening Moulton.” Bateson kept his voice low, desperate not to draw attention to this meeting. “What do you have for me tonight?”. The man, slight and pale, with a bald head and several days growth of beard, moved to the cart and lifted the tarp that was draped across it.

“Treasure I’d say, wouldn’t you?” There was a prideful, greedy, look on Moulton’s face as the doctor gazed at the contents of the cart. Bateson kept his excitement well hidden. He knew this game well.

“Interesting, to a point, I suppose. Do you have anything else?” Moulton looked wounded – exactly as the Doctor wanted. “Anything else?! Look at it! What more could you want?” He swept back the cover completely, exposing the‘treasure’ fully.

On the cart, on a bed of kelp and bladderwrack, was the corpse of a man. Young, perhaps in his 20s, fit and strong with defined muscles across his chest and arms. He was bearded and long-haired, his eyes the cloudy opal of Pallor Mortis.

It wasn’t the man’s upper body that was causing Moulton to dance from foot to foot like an excited child, it was the anatomy below the waist. Bateson’s eyes widened.

The man’s hips disappeared in to a single, pale, smooth limb. A tail, put simply, like that of a Beluga whale, ending in a fluke a yard and a half wide. A mer-man.

Like the Belugas, beneath the surface of the flesh you could see the echoes of ancestral limbs, joints protruding against skin and muscle, pressing out at angles not quite right.

The doctor reached out and touched this unholy chimera. The body was cold, the surface smooth, just like that of a cetacean. He pressed and his fingertips sank in to yielding tissue, leaving dimples when he removed his hand.

“A beauty eh doc?” Bateson had almost forgotten Moulton was there. “Yes. Quite.” He snapped out of his reverie, “Yes.It’ll do I suppose if you have nothing else to offer me. Deliver it to my lab now please Moulton, and avoid the harbour front, take the route below.”

“Same rates as last time doc?” he asked, the thought of rum springing to mind. “Yes. Same rate. Provided you deliver now, and quietly.” Bateson turned to leave before adding, “I’ll meet you at the door by the slipway.”

The doctor wiped his hands on a cloth. The talk of money grubby and trivial in the presence of such a specimen.

Moulton covered his prize once more, and swept past the doctor in to the mist. Bateson took a different, more direct route back to his workshop.

When he entered, he turned on the gas lights that illuminated the entrance in a curious red glow, passed through an antechamber and unhooked the bars from a door at the rear.

This entrance, unlike the one the doctor had used, was hidden among wood piles by a slipway near the Whalers Wharf. Almost always in shadow, and looking like nothing more than an old, barnacled slab of driftwood, the door was almost invisible.

Peering out in to the fog, Bateson watched as Moulton braced himself against the cart as he navigated the slope of wet cobbles. He slipped twice, but managed to stop his delivery from ending up in the harbour.

Bateson stepped back and Moulton and his cart moved past him, bringing a swirl of mist into the workshop. Through the low, stone tunnel, and in to the chamber directly outside the doctors lab where fisherman paused expectantly.

Far enough. Few in Innsmouth knew of Bateson’s workshop. Fewer still had been invited inside. Nobody entered the lab except the doctor.

“Here. Now get out quietly, push the door closed behind you.” Moulton accepted the handful of notes eagerly, not bothering to count them, and was gone, back out in to the town, and bound for The Inn on the Rock.

Bateson transferred the body on to a steel trolley that had once been used at a psychiatric hospital in upstate New York. Some stains from its time there remained. Moulton could collect his cart next time he visited, hopefully with another‘treasure’.

Pressing a large rubberised button on the floor with his foot to open the doors, the doctor pushed the trolley in to the lab. Pausing a moment, to steady himself, Bateson reached up and pulled the cord operating the lights. The flickering red glow illuminated a sinister scene.

The laboratory was hemispherical. A brick dome serving as a ceiling. Cobbles lined the floor, polished through many years of use. In the centre of the floor a steel grill covered a drain, channels led to it from each compass point.

One side of the room was occupied by a large bench. Half taken up with volumes of books and papers, charts and anatomical maps, a typewriter at its centre.

The other half, separated by a section of sheet steel, was laden with an assortment of medical instruments, carefully laid out, or hung up, meticulously arranged by size and type.

The other side of the room housed a series of huge jars. Some were empty, but most were full of fluids which barely concealed the specimens within. Bateson gazed at his beauties.

At the far left, the body of a huge squid, tentacles sold off to a fishmonger, just the head and trunk remained. A huge eye pressed against the glass, staring eternally in to the centre of the room.

Next, a giant eel, its body coiled and knotted tight. Slime gathered at the base of the tank. The eel’s jaws were wired open, displaying a mouth full of long, glassy fangs.

The next specimen, occupying the jar nearer the centre, a mermaids purse. Those leathery sacs found on beaches that once contained a shark or dogfish embryo. This egg case was far larger though, and the shadow within it hinted at something almost human.

In the penultimate jar, a young woman floated, suspended by leather straps under her arms. Her hair splayed out in the liquid, revealing her neck and the pale blue gills at each side. Her legs, although human in shape, were covered in fish scales, right down to her webbed feet.

An empty jar came last, full of fresh, clear liquid. The glass recently cleaned and scrubbed. The lid was propped by the base, greased, ground glass to ensure a good seal. This would be the home for Bateson’s latest acquisition.

This was not the first mer-creature that the doctor had encountered. He’d witnessed a pod of them swimming in northern waters near the Lefoten Islands a decade earlier, and he’d had one a year ago in this very room. Each one a prize.

The doctor thought them ultimate organism, born of both sea and land. God’s creatures? He didn’t know about that. He didn’t know about God. At least not the most obvious one.

Bateson washed his hands at an old ceramic sink, water provided by an articulated hose that descended from the ceiling. Donning a waxed canvas apron, he strode to his workbench and selected a tray of instruments.

Pulling goggles over his eyes, red lenses giving him a ghoulish visage, he picked up a large scalpel, gazed at the keen edge, and set about his work.

*

Elsewhere that night, in the fog-swaddled town of Innsmouth…

In Leper’s Lane, rats began to congregate. Masses of black, squirming fur, tails knotted. They writhed around each other, more akin to shoals of fish than rodents. Eventually, all movement stopped, and from within the mound of bodies, a king appeared.

In the study of Doctor Wickinson, by the microscope, a vial of Clarence Bulkington’s blood sits. Divided clearly in two now, the sample no longer resembled blood. The upper two thirds of the vial was filled with a grey liquid that looked like nothing more than dishwater.

The lower third, ink black and thick. Something within it seemed to turn and shift. It caught the meagre light from a gap in the surgery blinds, and it glimmered like oil on water.

In two separate houses, on either side of town, young John Chapman and Jennifer Cochrane, most recent King and Queen of the Ocean, both woke suddenly, their eyes fixed on something distant and horrifying. Their twinned screams echoing across the night.

Behind the town and over the hill, the surface of the dew pond on Dover Farm shivers in the mist. Its surface forms strange ripples, patterns of a complexity no breeze or weather could explain.

Only a Great Horned Owl was witness to this display, its small brain unable to grasp its strangeness.

Three miles out to sea, aboard Lightship No 1, Betty Tilley was awake. Her sleep disturbed by strange dreams and the noise of some creature sliding along the hull of the boat. Scales, or fins, or spines, rasping against the timbers for long minutes in the darkness.

In a small room at The Inn on The Rock slept Truelove Brewster. He’d barely said a word since his return from the Black Reef, little more than to say thank you when Rose placed another bowl of stew in front of him.

His dreams were of a vast hall of crystal, endless in its scope, populated by shadows, and of a dark presence upon a throne of light.

On the Whaler’s Wharf, leaning against the railing, hands clenched tightly around the iron, was William Trevore. His was the hand that had launched the harpoon that killed the beast.

Now, in the night, he could see the arc that projectile had traced in the sky before plunging into the creature’s eye. The eye that haunted Trevore still.

As the harpoon struck, the eye seemed to expand to cover the heavens, and beyond it, another world William saw. A hard landscape of cold stone against a sky swirling with stars of every colour. He cold feel the heat leach from his body as he remembered it.

And then, in a flash it was over and the creature exploded. William, along with the rest of the town, was overtaken by that strange bubble of nothingness that had rendered everyone unconscious.

On the Black Reef itself, scene of the destruction of Yog Sothoth, and of Brewster’s missing hours, the bell tolled.

No wind stirred, no tide reached the bell, but still it rang. The clang of its iron ringing clear across the sea and over the town. In their sleep, the townsfolk stirred at the noise.

*

Chester Bulkington woke up from strange dreams. Raising himself up on his elbows, he listened to the faint sound of the sea calmly lapping against the quays and wharfs of the town. A waning moon shone brightly through the small attic window. The fog had lifted.

He walked out in to the hallway divided by the stairs that descended between his room, and that of his twin Clarence. There was no noise coming from his brother’s room. He crossed the landing and listened at the door. Silence.

Chester opened the door and leaned in, his brother’s bed was empty, the room was empty. The window by the bed was wide open, and the chill night air had settled in the room with a crisp clarity.

Crossing to the window, Chester slipped, his feet flying out from under him, landing him flat on his back. Chester groaned, the breath knocked out of him. He lay there for a moment, the cold floor against the bare skin of his back.

As he got to his feet, he almost slipped again. The floorboards were slippery and wet. Clarence’s bed too was soaked and glistening. Standing carefully, Chester could see a pattern.

The floor was wet with footprints. The bed was wet where his brother had laid. And the window ledge, by the bed, was gleaming wet in the moonlight.

From the window there was a drop of twenty feet to the cobbled street below. It was shrouded in darkness, and Chester couldn’t see a thing down there.

He rushed back to his room and dressed quickly. Downstairs he hurried to the door and out in to the street, grabbing a lantern to illuminate the alley. The dim light from the oil lamp was just enough to poke in to the shadows. The street was empty.

Directly below Clarence’s window, there was another puddle of slimy residue, but amongst the dirt and straw in the road, it was impossible to see which way his brother had headed.

Chester stood in the street, breathing hard. The stone cobbles cold and rough beneath his bare feet. He looked up again at the open window of his brother’s room before returning inside. In the morning, he’d visit Doctor Wickinson again.

•

Rorqual, a black-bellied, oil-stained, whaling ship, sat heavily in the water at the wharf. Its deck awash with gurry – that slime and oil and blackskin, left-over from the harrowing of a whale.

This though, was no whale remain. Strange things lay around the charnel house of the ship.

That might be a tentacle. That, an eye – but as big as a melon. Something there, glistening, feet like a giant toad. Strings of slime-covered spheres, eggs?, dripped lazily from the scuppers, pulsing nauseously.

As the mist lifted from the town, its sounds returned, and Innsmouth came to life once more. Aboard the Rorqual, the decks were sluiced and scrubbed, fleshy jetsam cast in to the harbour where fish small and large made meals of it.

On the wharf, watching his fellow whalers work, was Bartholomew Gosnold, thick coat buttoned up to his whiskers, woollen hat pulled down to his brow. He turned and looked towards the town. Everything looked remarkably normal.

The whalers’ wharf was being repaired. Scaffolding had sprung up around a couple of the taller buildings. The abbey looked more cock-eyed than ever, but it still stood, looking down at the town, casting a long shadow.

People were incredibly resilient, able to adapt so swiftly to the strangest of circumstance. The people of Innsmouth had proved themselves, across many years, to be more resilient than most.

They had to be.

Across the harbour, rushing towards the whalers’ wharf from Black Alley at the heart of the town, was Chester Bulkington. Bartholomew had heard of Clarence’s disappearance and fearing the worst had sent a few men to Chester to help with his search.

Given the way things were going, Gosnold wasn’t entirely sure that finding Clarence alive would be a good thing.

Looking back at the deck of the Rorqual, Bartholomew needed little reminding of how strange things were. As the fell flesh slipped from the ship in to the water, he wondered what else the Gods had readied for Innsmouth and its folk.

•

Bartholomew Gosnold appeared in the perfect circle of the looking glass. The distance from The Pins, to the Whalers’ Wharf reduced to the length of the brass tube. James Arnold wondered what Gosnold was thinking.

Setting the telescope back on the window sill, James turned putting the dawn light at his back. He hadn’t spoken to a soul since the incident, but news came to him anyway, by various means.

As the sun crept higher, and its light and warmth spread across the windowsill, spilling on to the carpeted floor, James Arnold retreated further in to the room.

Most assumed the Arnold House to be a hermit’s place, given how long it was since its inhabitant had set foot in town. Little did they know that this reclusion was for their own safety.

Better a life of solitude here on these rocks, than free to live amongst those people, amongst all that warm blood. Pumping through veins, deafening and drowning out every other thought.

Sitting down at the dining table in the centre of the house James could relax. There were no windows in this room, so during the day it was his place of calm and safety. Even after all these years, he still feared forgetting the power of the sun.

Across the table were laid out maps, letters, documents, legal papers, purchase orders… all manner of paperwork pertaining to the town of Innsmouth. It was by these means that James Arnold conjured meaning and intent, and made his plans.

When Innsmouth was still a small fishing village, James Arnold had lived in Boston. There he had fallen foul of his family, and eventually of society, due entirely to his own weaknesses and failings. He resolved then to separate himself from those he might harm.

He sold everything he owned and left Boston, and found himself in Innsmouth at its dawning as a prosperous port. He bought land, not in town, but at the edge of the sea that provided its riches.

On The Pins, four rocks that provided some shelter from the violence of the sea, he built a home. And when that home was finished, he commissioned a sea wall, to connect the Pins, and to better protect the harbour of Innsmouth. A reputation as an eccentric benefactor was born.

So little did Arnold have to do with the townsfolk in the following years, they all but forgot him, and his doings faded in to history. And, like much history, was whispered and twisted by time until it was almost myth.

When did he come to town? Nobody remembered exactly. Was it his father who built the house on the pins and the seawall? Nobody remembered. Did he have a family there upon the rocks? Nobody remembered.

That was fine with James Arnold. A reputation as a recluse, and a family history shrouded by time and silence suited him perfectly.

•

Lemuel Shaw looked down upon his bloated body and watched it twitch along with his heartbeat. That his heart was still beating was something of a minor miracle. Shaw was a big man, overfed, underworked, and pampered – prince-like – by his housekeeper Nancy Weston.

His hands, pale and fleshy rested upon equally pale and fleshy thighs. Veins seemed to take the most circuitous routes along his limbs, surfacing here and there in blue arcs like ox-bow lakes.

It was his fingernails that now troubled Lemuel. Usually clipped and manicured weekly by Mrs Weston, he’d kept them hidden since the event. At the base of his nails, where that pale hemisphere usually sat, now grew strange crystalline protuberances.

Each fingernail, and his toe nails too – not that he could see them past his expansive belly, but he could feel the mineral hardness – had growths upon them, in varying colours and shapes. Some looked like tiny mushrooms, others like barnacles, and some like mussel shells.

The colours ranged from dark blue-greys, to vivid greens and pinks. The mass on the fingernail of his right little finger, looked like nothing less than mother-of-pearl coral.

During the event, Shaw had been in the bath tub. Since that moment, well, since regaining consciousness and thanking the gods he hadn’t drowned, his fingernails had itched and nagged. Each passing day had brought further strangeness to his extremities.

Shunning the spectacle of the solstice ceremony to lay in the bath tub was not through any squeamishness – the deaths of two more children bothered him little. It was the artificial gravity and sombreness everyone affected that sickened him.

This town had been killing children for decades, it was long past time that they should stop hiding it behind songs and costumes. It was for the good of the town, and that should be enough.

Now the bloody whalers had thrown everything in to the air, along with that cursed harpoon, who knew what would become of Innsmouth and its people. The status quo was good enough. It worked. Peace and prosperity at the cost of a couple of children. People could always have more children.